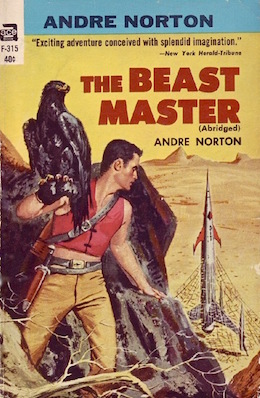

The Beast Master, published in 1959, is one of Norton’s most openly subversive novels. It’s well ahead of its time. Its protagonist is Native American, he’s deeply imbued with his culture, and it’s his resort to that culture which resolves the major conflict of the novel.

And it has me tangled up in knots. I can see why this was one of my all-time favorite Norton novels, right up there with Moon of Three Rings and The Crystal Gryphon. I loved it in the reread, too. And yet—and yet—

Our protagonist, Hosteen Storm, is the classic Norton loner-with-telepathic-animals in a universe that’s mostly alien to him. His world is gone, slagged by the alien Xik. He and his team (giant sand cat, pair of meerkats, and African black eagle) have helped defeat the Xik, but now they’re homeless, without a planet to return to. Storm has fast-talked his way to Arzor, a Wild West sort of place with terrain that somewhat resembles that of his lost Navajo country.

He needs a home and a job, but he has an ulterior motive for choosing Arzor. He’s hunting a man called Quade, whom he intends to kill. But nothing, including at least one of the planet’s human settlers, is as it seems.

Arzor is just about pure American Western. It’s a desert planet, where human settlers run herds of buffalo-like frawn, and the natives, called Norbies, roam the land in tribes.

Norbies remind me of Green Martians from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom, but bipedal, with the tusks moved up and turned into horns. Their vocal apparatus does not allow for human speech, nor can humans reproduce theirs. The two species communicate in sign language. Which Storm of course, being Native American, picks up instantly. Because Native Americans used sign language, and it comes naturally to him.

Most of the Norbies Storm meets are friendly to humans, but there’s a tribe from elsewhere that’s doing terrible things to the settlers. Not because the settlers are invading their lands—the tribespeople are the invaders—but because that’s just how they roll. And then it turns out that they’ve been framed, when they haven’t been manipulated, by Xik remnants who are trying to take over the planet.

Storm runs afoul of all this after taking a job wrangling horses for a traveling horse trader. These horses are a special spacegoing breed who happen to look just like Terran Appaloosas—a Native American breed. Storm tames a feral stallion and demonstrates tremendous equestrian competence. Because he’s Native American, and Native Americans have a natural talent for horsemanship.

Actually, Norton says it’s because he’s Navajo, but we’ll get back to that. His ability with horses is logical enough since he’s a Beast Master. The rest of his animals served him in the war, the eagle by air and the cat by land, and the mischievous meerkats as accomplished saboteurs. Storm communicates with them telepathically, though it’s very basic and not always reliable.

Storm meets Quade almost immediately, but aside from hating on him hard, doesn’t manage to carry out his plan of killing the man. He discovers, to his dismay, that Quade isn’t at all the villain he was expecting; in fact he seems honorable and he’s much respected—and he speaks Navajo. Quade has a son, to further complicate matters: a young man named Logan, who is at odds with his father, and who has gone off into the wild to live his own life.

When Storm’s job with the horse trader ends, he moves on to an archaeological expedition into the hinterlands, seeking out the mysterious Sealed Caves, which may contain evidence of an ancient starfaring culture. This recalls the Forerunner universe, but in that one, Terra was blasted by its own people rather than by aliens, and it’s still habitable. Storm’s Terra is completely gone.

The expedition fairly quickly finds a set of classic Norton ruins, but is equally quickly wiped out by a flood which also takes one of the meerkats. Storm, a young Norbie guide named Gorgol, and the rest of the animals survive and discover that, indeed, the Sealed Caves contain a mystery: multiple habitats from numerous worlds, including Terra.

We never find out who built these or why, but they have magical healing powers—another Norton trope—and they serve as a refuge when Storm and company discover the Xik invaders. The Xik have a captive whom they seem to value, who turns out to be none other than Logan Quade. More: Logan bears a striking resemblance to Storm.

Storm rescues Logan in a bravura move: he walks openly into the native camp with his eagle and his cat and his meerkat on full display—claiming them as his totems, especially the eagle which is analogous the tribe’s animal totem—and chanting in Navajo. The natives are so nonplussed, and so impressed, that they don’t immediately cut him down.

Once Storm is in, Gorgol provides a diversion, allowing Storm to rescue Logan and take him to the caves to be healed. But as they approach the entrance, they realize the Xik ship is trying to take off. By sheerest luck and the vagaries of its highly retro design (it has tubes!), it blows up.

There’s no rest for our doughty protagonist. He drops Logan off in the cave and heads back out to mop up the survivors. By this time Quade and the cavalry—er, settlers have arrived.

Storm ventures forth, has an exciting knife fight with the Xik agent in human disguise who has been stalking him since he arrived on the planet, and passes out even as he wins the battle. He wakes up in Quade’s care, and we finally learn why Storm hates him so much.

Storm was raised by his grandfather, a Dineh (Navajo) elder to told him his father was killed by Quade and his mother was dead. Quade tells him the truth: that the grandfather was a fanatic, and Quade did not murder Storm’s father. In fact Quade (who is part Cheyenne, so also Native American or as Norton calls them, Amerindian) was his partner in the Survey Service. Storm’s father was captured and tortured by the Xiks, and was never the same again; he escaped from the hospital and headed home to his family.

Storm’s mother knew something was wrong and told Quade where he was. By the time Quade got there, he had fled again; they found him dead of snakebite. The grandfather blamed them for betraying his son, told them Storm was dead, and drove them off.

They left together, eventually married, and Logan is their son, which makes him Storm’s half-brother—and which explains why they look so much alike. She died four years after Storm’s father.

The grandfather meanwhile told Storm a completely different story, and raised him to hate Quade and rage against his mother’s shame. In time Storm was forcibly removed and sent to school, though he was able to visit and learn from his grandfather in later years. He went on to join the Terran military and become a Beast Master, and here he now is, with his life’s purpose revealed as a lie.

Now that we know the truth about Storm’s history, we get a patented Norton rapid wrap-up. Storm processes briefly, wibbles dramatically, then accepts Quade’s welcome into his family. The proof is Logan, who appears draped in Storm’s animals, all of whom have bonded to him. This is wonderful, Storm thinks. Finally, he has a home.

This really is one of Norton’s best. She’s trying her utmost to portray a Native American protagonist from his own perspective. To the best of her knowledge and ability, she respects his culture and traditions, honors his beliefs, and presents a surprisingly unvarnished view of the horrors perpetrated on Native Americans by whites.

She actually goes there with the abduction of a child and his forcible education in mainstream culture. She portrays the conflict between the elders and the assimilated youth. She comes down on the side of preserving the language and the rituals, though her portrayal of the grandfather tilts toward the negative: he’s a fanatic, he’s relentless, he “tortures his own daughter” and lies to his grandson. The overall sense is that an assimilated person can live a productive life in mainstream culture, but he can keep his own traditions.

That’s radical for 1959. In the Sixties when I first read the book, I was enthralled. I loved the noble and grandly epic portrayal of the native language and culture, I learned what I thought was a fair bit about them, and I understood that the future wasn’t all white or colonist-American. It was one of the first tastes I had of what we now call diversity, and it whetted my appetite for more. I wanted my future to be full of diverse cultures and languages and ethnicities.

In 2018, I can see all too clearly why we need the Own Voices movement, and how Norton’s ingrained cultural assumptions caused her to fall short of what she was trying to do. Even Storm’s name—Hosteen is a title, an honorific. She named him, essentially, Mister Storm.

That’s the sort of basic error that happens when a person tries to do her research but doesn’t realize how much she doesn’t know. The same thing happens with Storm and horses. The Navajo have them, and it’s true they’re a warrior culture, but the great horse cultures were the tribes of the Plains, including the Cheyenne, from whom, somewhat ironically, Quade is descended. As for the horses, they’re a breed developed by the Nez Perce, yet another tribe with its own distinct language and traditions.

Storm makes a lovely epic hero, but there’s an uncomfortable amount of stereotyping in his portrayal. He’s the Noble Savage, soft-spoken when he’s most enraged, and genetically predisposed to bond with animals, train horses, and intone sacred chants.

To add to the squirm level, Arzor is a straightforward late-Fifties Western set, with dusty frontier towns, traveling horse traders, contentious cattle barons, and two flavors of native tribes, the friendlies and the hostiles. The Norbies are TV Indians, speaking their sign language in traditional broken English (“I come—go find water—Head hurt—fall—sleep”). They’re Noble, too, even the hostiles, but they’re not quite up to the level of the settlers.

There were just a few too many unexamined assumptions for my comfort as I reread, but even more than that, I had trouble with Storm’s complete failure to pick up on the irony of his position. He has no apparent trouble with the way he was separated from his grandfather. He doesn’t resent what was done to him, though he’s perturbed enough when he realizes his grandfather lied to him.

Nor does he seem to see the close parallels between the history of the American West and the situation on Arzor. Norton is careful to tell us that the natives are fine with the settlers being there, the settlers aren’t really stealing Norbie lands and livestock, and there’s no deliberate conflict between them—what conflict there is is drummed up by the alien Xik. It’s a happy invasion, fat-free, gluten-free, and free of inherent conflict.

Storm gets along well with the natives, but he doesn’t make any connection between them and his own people. He’s totally invested in being a settler, joining a ranching family, eventually getting his own spread. It never dawns on him that on this planet, he’s taking the role of the whites on his own lost world.

He’s missing the many layers and complexities of the Native American relationship with white culture. Sometimes we even see why: Norton describes him from outside, how he doesn’t realize how dramatic and noble and Other he looks. She’s doing her best to give us a genuine and lovingly portrayed non-white character, but she’s still a white American lady in the 1950’s, with all the ingrained biases that go with that identity. (Not to mention the notable lack of living human or native females—but that’s a feature of all of Norton’s work in this period.)

I do still love this book, but I’m too conflicted to be comfortable with it. I would not refer a young reader to it without a whole lot of caveats and a recommendation to read the work of actual Native American writers. It’s a good adventure story, the characters are memorable, and for its time it’s extremely progressive. But we’ve come a long way since.

Next time I’ll move on to the sequel, Lord of Thunder, which was also a favorite of mine—and no doubt has similar problems. We’ll see.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her new short novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published last fall. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.